Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

Why Growth Matters (2 page)

Figure 1. India: Low and stagnant growth rates despite rising investment-to-GDP ratio

Source: Author's construction based on data from the

Handbook of Statistics on India's Economy

, 2012, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai

Figure 2. Soviet Union: Booming investment, collapsing growth

Source: Authors' construction based on data in Desai, Padma, 1987,

The Soviet Economic Slowdown: Problems and Prospects

, Oxford: Basil Blackwell

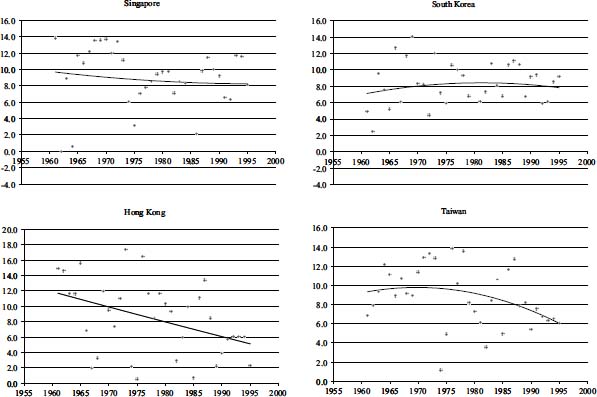

By contrast, the East Asian economies registered extremely high investment rates but the investments were productive and thus the result was extraordinarily high growth rates, generally described as an “economic miracle” (see

Figure 3

). The investments were associated with extraordinary export performance, which resulted in imports of equipment embodying advanced technology.

5

So what were the elements that reduced India's growth rate to almost 3.5 percent annually over nearly three decades spanning 1950 to 1980? Four factors played a critical role:

6

Figure 3. High growth rates in South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong in the 1960s and 1970s

Source: Authors' construction based on data from World Bank's World Development Indicators online (accessed on November 14, 2012)

Â

1.

Â

There was an extensive system of controls over private investment and production. For example, industrial licensing regulated expansion of production, even its diversification;

7

import licensing regulated all imports; investment licensing regulated expansion of new capacity. The result was a Kafkaesque maze of regulations that stifled any innovation, production, and investment, while also encouraging inefficiency because effective competition from domestic entry of new firms and from imports was virtually eliminated.

Â

2.

Â

The public sector was steadily expanded and even granted monopoly in many activities that went beyond the conventional areas, such as utilities. In turn, these public enterprises predictably resulted in inefficient production and associated losses that also imposed a revenue burden on the state.

8

Â

3.

Â

Obsessive self-sufficiency defined trade policy. Domestic manufacture, once licensed, was automatically protected. The trade economist W. Max Corden has called this “made to measure” protection.

Â

4.

Â

Similarly, India restrained direct foreign investment, which fell to dramatic lows during this period. When the reforms began in earnest in 1991, foreign investment flow amounted to barely $100 million, which is hard to believe for a country of India's size.

Two central follies stood behind the policy features that undermined growth:

First, the heavy hand of the government in economic activity was so pervasive that one of us had remarked that the problem with India (and many other developing countries) prior to the reforms of the early 1990s was that Adam Smith's Invisible Hand was nowhere to be seen.

Economist Joseph Stiglitz and financier George Soros talk of “market fundamentalism” as having been practiced when liberal reforms were introduced. In truth, in India the reforms represented a move to the pragmatic center from a situation in which markets were sacrificed, with

grave consequences in efficiency and growth, to what can only be described as “anti-market fundamentalism.”

Second, the counterproductive policy framework was also inward-looking on trade and hostile to direct foreign investment (DFI), which meant that India turned away from integration into the world economy, forgoing important gains from taking advantage of such integration.

9

The proponents of autarky in trade were of the view that, as the Chilean sociologist Oswaldo Sunkel put it, “integration into the international economy would lead to disintegration of the national economy.” This “malign-impact” view of opening to trade turned out to be generally wrong.

While the favorable experience of East Asia was built partly, in Singapore and Taiwan, on a pro-DFI policy, with DFI leading to multiple benign effects such as diffusion of know-how to local entrepreneurs, the same was not true of South Korea, which followed instead the Japanese-style policy where technology was imported instead. India did neither effectively. No benefits were derived from a general skepticism about DFI and the absence of an active technology-importation policy.

Reforms led to growth in India in exactly the same way as in Brazil after President Hernando Cardoso, who as an academic sociologist had opposed globalization as leading to dependency (this is the famous

dependencia

thesis), took Brazil toward globalization. The same happened in China, starting in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Some economists, such as Dani Rodrik, have argued that economies have grown despite embracing anti-trade policies and disregarding markets, so it is wrong to attribute success on growth to these liberal and pro-trade reforms. But this claim is hollow because there is no compelling case where such policies led to significant growth over a sustained period. This was particularly true of the Soviet Union, where growth rates were high for nearly two decades but then declined steadily as the autarky and the absence of market-based incentives steadily undermined the economy.

The old saying insists that economists never agree, but the late Joan Robinson, a radical economist from Cambridge who admired pre-reform China, and Gus Ranis, the mainstream Yale University economist, were overheard astonishingly agreeing on how remarkable Korean development was. It turned out that she had North Korea in mind, whereas he was thinking of South Korea. Of course, down the road, she turned out to be wrong. The North Korean autarkic and heavily anti-market developmental strategy could deliver missiles and nuclear weapons, but not sustained overall development. South Korea, which instituted “liberal reforms,” grew steadily.

The growth in China in the late 1970s and early 1980s was also led by the elimination of collective farming and the introduction of incentives to peasants. Subsequently, in response to sustained opening of trade and foreign investment, there followed the enormous expansion of exports from Guangdong province in the southeast, with large inflows of DFI and technology absorption resulting in an expansion of Chinese income and growth rate. A movement away from antimarket fundamentalism through the introduction of promarket policies and the removal of the disincentives against trade and DFI lay at the heart of the economics of Chinese gains in productivity and enhanced growth.

The East Asian miracle was also based on outward orientation in trade. The phenomenal growth in exports followed the deliberate integration into the world economy. Whereas India followed a policy of near-autarky in the pre-reform 1960s and 1970s, the East Asian economies looked ever more globally.

10

As a consequence the Indian industry was constrained by the internal domestic demand. This meant that the inducement to invest in industry was constrained by the domestic expansion of agricultural incomes. But since agriculture rarely grows at a sustained rate in excess of 4 percent in historical experience, the East Asian decision to exploit foreign markets meant that the inducement to invest was not so constrained. Investment expansion on a dramatic scale followed and the expansion of exports that was its flip side meant also that East Asian economies could import capital goods that embodied advanced technology.

This in itself would not have been enough, however, to generate extraordinarily high returns and associated growth. To get the most out of the new technology, the workforce had to be literate enough to work with the advanced machinery. If not, the embodied technical progressivity would have borne no fruits. Thus, for example, the older of us has a DVD player with the latest features, but he is able to play only Start and Stop on the remote control; the productivity of his DVD player is the same as if no technical progress had been embodied in his state-of-the-art machine.

East Asia fortunately enjoyed, partly as an unintended benefit of Japanese occupation and the example of Japanese tradition of educating the massesâsee the splendid autobiography of Junichiro Tanizaki (1988), arguably Japan's greatest writer, which describes his school experiencesâa primary and secondary education commitment that assured East Asian countries of astonishingly high levels of literacy. Besides, countries such as Singapore and Hong Kong freely imported skilled manpower at higher levels, making up for absent indigenous skills by importing foreigners with skills, and simultaneously sending masses of natives abroad to top universities to acquire the skills in the meantime and bringing them back at high remuneration. Benign attitudes toward trade and DFI combined with high and productive investment rates, importation of equipment with embodied know-how, and its successful exploitation by a highly literate population in a policy framework that additionally permitted incentives and rewards, created a virtuous circle that produced the East Asian miracle. But central to the phenomenon was the outward orientation in trade.

The experience of China, India, and East Asiaâwhose population amounts to not quite half of the global total populationâdemonstrates how growth is stimulated and sustained within the policy framework that exploits the opportunities provided by integration into the world economy, and also relies on a sophisticated use of market incentives in guiding production and investment.

11

Conversely, they also demonstrate that a shift away from such a policy framework undermines growth.

Three important caveats must be kept in mind. First, the liberal policy framework that has produced prosperity is not libertarian, nor is it one of “market fundamentalism.” For instance, it allows environmental objectives, such as reducing domestic pollution, while proposing the use of price-based instruments, such as emission taxes instead of direct quantitative controls. If producers of a good can simply dump waste into a lake or a river in the country, that will lead to overproduction of the good since the private cost to the producers will be lower than the social cost, which should not ignore the damage to the environment. We therefore need a polluter-pay tax, which puts a cost on the discharge of pollutants. The correct way to diagnose this issue is to say that we have a “missing market” regarding pollution, and in effect the tax creates that market. You do not have to be an ideologue of markets to embrace it as part of the appropriate policy agenda.

Second, openness in trade is only an enabling mechanism. If other domestic policies create obstacles to taking advantage of the trading opportunity, the gains from trade will be minuscule. If domestic restrictions on production and trade prevent investment in new capacities to undertake exports, any opening to trade would have been frustrated: gains from trade could not be obtained in any significant way if resources could not be pulled toward the export industries, old and new. To use an apt analogy, if a door is opened but you do not have traction in your legs, you will not get through that door.